Et oui les DVD sont hors de prix, je regrette vraiment de ne pas les avoir acheter à l’époque

Tu es sûr de ta mémoire ?

Imdb indique bien Que sera, sera : "Dead Like Me" Pilot (TV Episode 2003) - Soundtracks - IMDb

Bon, n’ayant vu la série qu’en DVD, je ne connais que cette version (il faudrait, d’ailleurs, que je voie la deuxième saison, un jour).

Tori.

Sur ce coup oui

C’est la version américaine d’Un indien dans la ville ?

Tim Allen.

Super comédien.

Ça fait mal au cœur.

D’autant que, à titre personnel, les symptômes évoqués rappellent.ceux que mon père a subis, alors que la famille l’a souvent comparé pour rire à l’acteur. Le destin est étrange parfois.

WHEN DID IT JUMP THE SHARK « Here’s one of the great debates in TV history, because historically, people tend to say it is when David and Maddie got together, and that myth has been so powerful that we’ve now seen DECADES of showrunners pointing to David and Maddie sleeping together as the reason why they won’t get together the “Will they or won’t they?” characters on their show, and that’s such crap. The show didn’t fall apart because of Maddie and David getting together, it fell apart because of behind-the-scenes reasons that led to Maddie and David being separated for most of Season 4 (Shepherd was having twins and Willis was filming Die Hard), and when they finally get back together, Maddie spontaneously married another man, ostensibly to add tension to the show, but instead just made it a big ol’ “What are you DOING?” situation. Maddie then having a miscarriage of her baby with David at the start of Season 5 was rough, too, but I think the abrupt marriage to another man was the point the show jumped the shark. It got even worse in Season 5, but that’s the shark-jumping moment for me. »

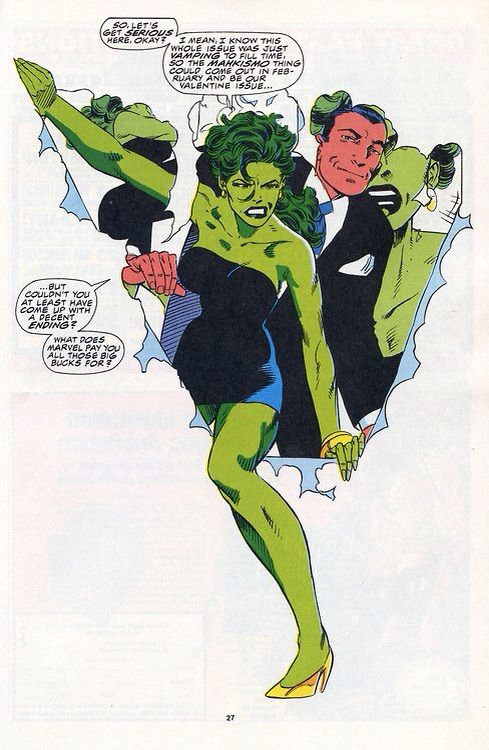

Steve V : « I know you were probably just starting out when these were published but-- Do you have any insight on the direction characters like She-Hulk and Animal Man took in the late 80s/early 90s? Meaning breaking the fourth wall/aware they are fictional characters while still coexisting in their mainstream continuities? I just finished Grant Morrison’s Animal Man and realized it came out around the same time as John Byrne’s Sensational She-Hulk. It’s fascinating to see DC and Marvel tackle the same concepts side by side, one comedic and the other more existential and horrifying. Obviously this wasn’t a new concept at the time or since. Stan and Jack (and others) did this sort of thing for gags since the golden age. Deadpool. Mark Waid’s FF run dabbled a bit with it in the afterlife. Mark Millar’s 1985. There are countless examples in comics and other mediums. But Shulkie/Animal Man seem like the modern watershed moment for it in superhero comics continuity (as far as I know). »

Tom Brevoort : « The breaking of the fourth wall is a bit that comics, and indeed, other media, have been doing pretty much since media was invented. But I think the missing link that you may be overlooking here is the popularity in the late 1980s of the television series MOONLIGHTING . i can’t speak for Grant and ANIMAL MAN , but John Byrne was very forthcoming at the time that he was inspired to take the fourth wall-breaking approach to his new SHE-HULK series by MOONLIGHTING doing the same sort of thing. That show popularized the approach at the moment, and as is often the case, those working in the comic book field were inspired to follow suit. »

Piqûre de rappel :

The implicit promise of the streaming era is that everything you could possibly want to watch can be accessed in an instant, the endless, all-you-can-eat bounty of Hollywood just a click (and a subscription fee) away.

Try telling that to Glenn Gordon Caron.

A veteran TV producer, Caron created the 1980s detective series “Moonlighting,” which earned critical acclaim and strong ratings in its day for its innovative blend of fourth-wall-breaking screwball comedy, mystery and romance. Over its five-season run, the series pulled in 41 Emmy nominations, influencing many shows that followed and launching a previously all-but-unknown Bruce Willis — whose snappy, sexually charged banter with co-star Cybill Shepard captivated viewers — to megastardom.

But despite years of lobbying by Caron, “Moonlighting” has yet to appear on any streaming platform, held up by the high cost of clearing the rights to the large amount of music used in the show. Caron has felt an even greater sense of urgency since Willis was diagnosed last year with frontotemporal dementia, ending his legendary career.

“I’ve been campaigning since about 2005, saying, ‘What can we do to get it back in circulation?’” says Caron. “It’s frustrating — there are bootlegs and stuff on YouTube, but the show has been almost impossible to watch. When I saw that Universal was able to get ‘Miami Vice’ out there — another show that’s larded with music — I thought, ‘Gosh, there’s got to be a way for us to do it.’”

More than a decade into the streaming era, the case of “Moonlighting” is hardly unique. Despite the seemingly infinite sea of content on an ever-expanding array of platforms, many cherished films and TV series remain unavailable to stream, caught in a tangled web of licensing quandaries, rights disputes and ever-shifting corporate strategies.

The list of films absent from the streaming landscape includes classics (Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 Gothic thriller “Rebecca,” Elaine May’s 1972 rom-com “The Heartbreak Kid”); cult favorites (George Romero’s “Dawn of the Dead,” David Lynch’s “Wild at Heart,” “Pink Floyd: The Wall”) and crowd-pleasers (“The Cannonball Run,” “Cocoon”). Iconic TV shows like “thirtysomething,” “Northern Exposure,” “L.A. Law” and “Homicide: Life on the Streets” are similarly nowhere to be found.

As for “Moonlighting,” to Caron’s great relief, the Walt Disney Co., which owns the rights to the series, is finally preparing to launch the show onto streaming soon, though the details are still being ironed out. “I don’t know where we will end up, but with any luck we’ll see it before the end of the year somewhere,” Caron says.

As he sees it, the show’s belated arrival on streaming comes not a moment too soon.

“I think it was approaching that moment where it probably would have left the zeitgeist if we didn’t do something soon,” Caron says. “You know, you sort of move from popular to cult to forgotten. I think right now we’re in the sweet spot.”

Maintenant faut espérer voir cela en France que ce soit en SVOD ou BR

"In the world of television, good TV pilots are fascinating little things. This is because a good TV pilot does not necessarily a good TV series make. It’s one of the strangest little things, where the first episode of a series being really good doesn’t always speak to the quality of the series as a whole. This is often because the first episode is sometimes treated like a little movie (often, they’re even two hours long) and they sometimes have bigger budgets than the rest of the series.

Sometimes, though, those great pilot episodes foretell a great TV series, and in the case of Moonlighting, I think that that is definitely the case, but in a lot of ways, I think the pilot might even be sharper than a typical episode of Moonlighting. One of the big critiques of Moonlighting is that it eventually got TOO loose. The joking stuff was HUGE at the time, practically revolutionary (I think I’ll write a piece of just HOW dramatic the effect Moonlighting had on TV in the near future), and yet, as with a lot of other concepts that were revolutionary when they debuted, there was almost a sense of it being TOO revolutionary, in that the show sort of went back to the same well a bit too often.

That’s a small critique, though, as Moonlighting, in general, is a great show, but it’s worth noting that it was rarely ever as tight as in its first season, and that first episode is as tight of a story as anything in the series’ run.

The March 1985 pilot, written by show creator Glenn Gordon Caron, and directed by the late, great Robert Butler (the man who said, as I noted in this old TV Legends Revealed, “Hey, what if, instead of Remington Steele just being a fictional character, he is instead INTENDED to be fictional, but then a dude shows up saying that he IS Remington Steele?”) sets up the brilliantly clever concept of the series. Maddie Davis (Cybill Shepherd), a famous model, has all of her liquid assets stolen by her business manager. All she has left is her NON-liquid assets, including a number of small businesses that she owns as tax shelters. Her accountant tells her that she has to quickly sell off the small businesses, but when she goes to sell off the detective agency she owns, David Addison (Bruce Willis), the guy who runs the agency, tries to convince her not to sell, and then they get caught up in an elaborate scheme involving Nazi diamonds, and in the end, they have saved the day and Maddie decides she will keep the agency, but run it WITH David, and hilarity (and romance) ensues.

The series was intended to be a modern day update on the old romantic comedy mystery banter films like His Girl Friday and The Thin Man, where the romance is a centerpiece of the film, but so is the mystery and so is the banter between the romantic leads. That was what Moonlighting was about, and in Shepherd and Willis, the show got essentially two movie star quality actors with dynamic chemistry. Paired with clever scripts, the series was an utter delight.

But it was particularly delightful in those early, tight episodes, where there was still room for some wacky stuff (they literally do a sort of silent movie slapstick thing with a ladder hanging from a building, and Maddie hanging from a giant clock hand), but it was relatively restrained, and better supported (and not just sort of out of nowhere like the show sometimes would do).

If all we had was just that first episode, we’d have had an entertaining TV movie that people would still remember fondly to this day (and would probably have been remade and/or turned into a TV series, since there was so much there to work with), but luckily, we had a lot more than just the first episode. The first episode was still great, though !"