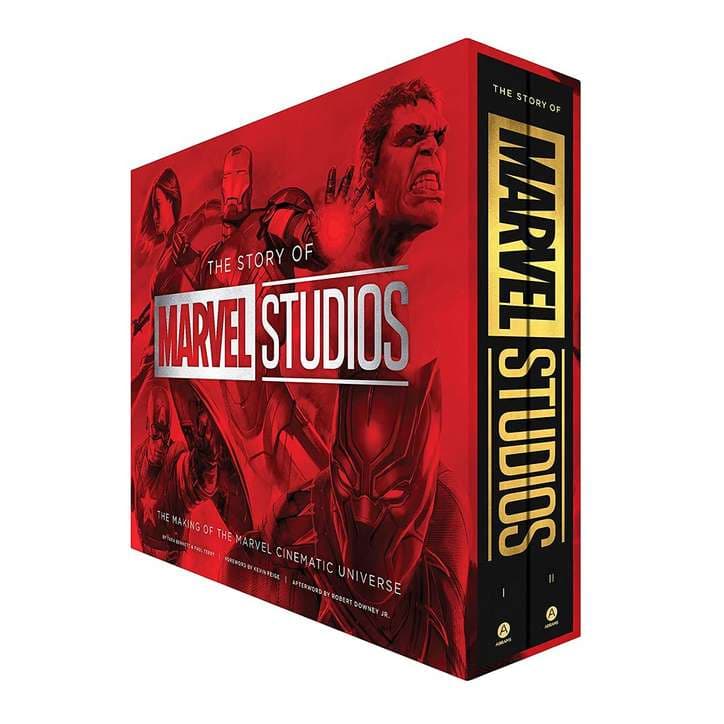

Aujourd’hui est un grand jour pour nous, en effet, nous vous présentons notre projet Marvel le plus fou : un double ouvrage collector sur le making-of des 23 films de l’Infinity Saga, réunis dans un coffret et entièrement en français. Un objet majestueux aux finitions haut-de-gamme et pour lequel nous allons avoir besoin de votre soutien .Pour en savoir plus, RDV ci-dessous.

https://welcome.kisskissbankbank.com/dans-les-coulisses-de-marvel-studios/

Source : page Facebook de l’éditeur

C est conseillé ?

Si c’est Jim Lainé qui a traduit, oui, forcément. Il a besoin de bois pour l’hiver, avec le prix de l’énergie qui augmente.

Je n’ai pas eu cette joie.

Et je me tâte pour demander un exemplaire à l’éditeur (sachant que je n’aurai que le temps de le feuilleter, et sans doute pas la place pour le ranger).

Jim

Je connais un jeune fan que cela pourrait intéresser alors

Héhé.

Je vais trouver de la place.

Jim

Un ouvrage qui doit faire le bonheur de certains internautes puisque les informations qu’il contient alimentent pas mal d’articles ces jours-ci.

Pas besoin d’un article ni d’un livre pour remarquer que l’Agent Carter était canon.

Jim

Est ce que ça a été lancé ce livre ?

Pour noel ce serait bien.

Pas reçu de notification.

C est bien ça.

Merci

2022 ?

Tori.

Voilà

Voici les dernières nouvelles :

Il y a quelques mois, nous vous avons annoncé le lancement prochain d’une campagne sur KissKissBankBank pour traduire le mastodonte Dans les coulisses de Marvel Studios. Suite à cela, vous avez montré un enthousiasme pour le projet qui nous a fait chaud au cœur et pour lequel nous vous remercions tout aussi chaleureusement.

Malheureusement, les Studios Marvel ne nous autorisent finalement pas à lancer une telle opération sur cette plateforme, malgré tous nos espoirs et nos efforts.

Comme vous le savez, il est dans notre ADN de publier en français les plus beaux ouvrages dédiés à l’univers Marvel.

Ainsi, nous avons tout de même décidé de nous lancer dans cette aventure, avec pour objectif de faire paraître ce coffret en fin d’année 2022.

Nous espérons pouvoir compter là encore sur votre soutien. Merci encore à tous pour votre engouement autour de ce projet.

L’éditeur a annoncé l’abandon du projet pour diverses raisons… Dommage.

"Consider another origin story, hitherto ignored. One late-summer weekend in 2003, a talent-agency executive named David Maisel was in his sweatpants, in the loft of his L.A. apartment. He had spent two years at the Endeavor agency, and he was contemplating his next move. But he didn’t want to remain an agent—he wanted to run a studio. “That’s when I thought, Hey, if I can get a movie I can believe in, and every movie after that one is a sequel or a quasi-sequel—the same characters show up—then it can go on forever,” he told me. “Because it’s not thirty new movies. It’s one movie and twenty-nine sequels. What we call a universe.” He eyed the Marvel comics on his bookshelves. This, Maisel claims, was the birth of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Maisel, a slender and soft-spoken man, was telling me this story in the spot where the eureka moment took place. I had met him at his nearby office, a second apartment, festooned with Marvel posters, action figures, and director’s chairs. He wore cargo pants and a Silver Surfer hoodie. Without him, he said plainly, “the M.C.U. would never exist. It’s like a Thanos snap.” Near a plastic Thor hammer was a framed Times article from 2007, detailing Maisel’s plans for Marvel to release “10 self-financed films in the next five years.” Feige, Maisel noted, was not even mentioned. “Most people right now think Kevin started the studio,” he said. “They don’t know me at all.”

“David’s been sort of written out of the history of the studio, which I really think is weird,” John Turitzin, who until recently was Marvel Entertainment’s chief counsel, told me. “It was his brainchild.” Although Maisel came up alongside such Hollywood wheeler-dealers as Bryan Lourd, he has a gentle, almost childlike air. He is single and unextravagant, describing himself as “very influenced by Buddhist philosophy and simplicity.” He had spent the previous three years living with his elderly mother, who died eight weeks before we met. But he’s not without ego. “He thinks that he’s the smartest guy in the room all the time—just ask him,” a Marvel alumnus told me. “Because he’s really smart and myopic, he doesn’t read the room very well.” If Maisel were a Marvel character, he’d be a mysterious sorcerer in a cave, whispering to all who entered that he created the solar system.

Maisel grew up in Saratoga Springs, the son of a dentist and a Czechoslovakian-born housewife. “Marvel comics, and especially Iron Man, were my favorite things,” he recalled, sitting on a sofa with Iron Man throw pillows, his feet on a Spider-Man rug. Tony Stark had a cool suit and a captain-of-industry swagger, but “he had a frail heart.” In the eighties, Maisel tried to rally his classmates at Harvard Business School to “go buy Marvel,” but the idea didn’t get further than a brainstorm over beers. He worked for consulting firms, but after his sister died, of lupus, he realized that “life is precious” and moved to Hollywood, where he got a job with the superagent Michael Ovitz, the co-founder of C.A.A. “He needed his token Harvard M.B.A. that he could bring with him to Warren Beatty’s house,” Maisel said. When Ovitz became the president of Disney—a tumultuous sixteen-month tenure—Maisel followed him and did strategic planning at ABC, which was owned by Disney and run by Bob Iger. “I learned, at Disney, the power of franchises,” Maisel recalled. He joined Endeavor at the beckoning of the firm’s partners Ari Emanuel and Patrick Whitesell. In Hollywood, Maisel was living in the Tony Stark fast lane (he and Leonardo DiCaprio have taken their moms out together for Mother’s Day) when he determined that Marvel should finance its own intertwining movies. The problem was that he didn’t work at Marvel. Maisel flew to Palm Beach to pitch Perlmutter over lunch at Mar-a-Lago. (Donald Trump, a friend of Perlmutter, who later became one of his major political donors, came by to say hello. “I don’t remember what Trump said at the time, but it was nothing impressive,” Maisel recalled.) Perlmutter was skeptical; he saw movies primarily as an engine to sell merchandise. But that hadn’t always worked out. In 2000, Fox moved up the release date for “X-Men” by six months, leaving Marvel without action figures in stores. The former Marvel executive I spoke to recalled, “David had a sense that, if Marvel could own its own movies and control its destiny, it would change the course of cinema history.”

Perlmutter agreed to let Maisel try, appointing him president of Marvel Studios. But there were hurdles. When Maisel pitched the board of directors, they said no—or, at least, not as long as there was any financial risk. Maisel asked them to halt movie licensing for six months while he put together the money. Turitzin recalled that, at a meeting with Standard & Poor’s, to get a credit rating on the financing, “David made a comment about how Marvel was a compelling brand that people wanted to see on the screen, and the woman who was running the meeting for S. & P. spontaneously guffawed, because the idea seemed like such hubris.” Marvel would have to compete not only with DC’s Superman and Batman but also with its own best-known heroes, Spider-Man and the X-Men, which were licensed to other studios. “If I had gone there even eight months later, it would have been too late, because they were about to license Captain America and Thor,” Maisel said.

Like Nick Fury assembling the Avengers, Maisel lassoed back whichever characters he could. He recovered Black Widow from Lionsgate. He struck a deal that let Universal keep the right to distribute a Hulk movie but had a loophole allowing Marvel to use the Hulk as a secondary character. (This is why, even though the Hulk is all over the M.C.U., Marvel has never released a “Hulk 2.”) New Line, with pressure from Avi Arad, reverted its rights to Iron Man, hardly an A-list hero. To prove the viability of its characters, Marvel released direct-to-DVD animated Avengers movies. In the pre-recession boom times, Maisel secured five hundred and twenty-five million dollars—enough for four movies—in risk-free financing through Merrill Lynch. The collateral was the film rights to the characters, which, if the movies failed, would presumably be worthless anyway. “It was like a free loan,” Maisel said. “You go to a casino and get to keep the winnings. You don’t have to worry if you lose. The board had really no choice but to approve me making the new Marvel Studios.” Marvel convened focus groups of children, who were shown the available superheroes and asked which one they’d most want as a toy. The answer, surprisingly, was Iron Man.

At the Marvel Studios offices, now above a Mercedes-Benz dealership in Beverly Hills, a team of mostly Gen X men who had grown up on Marvel comics—including Feige and Avi Arad’s son, Ari—planned the first slate of movies, which would introduce the heroes one by one, and then unite them in “The Avengers.” (Anyone bemoaning Gen X’s supposed lack of cultural influence should look to the M.C.U.) “There was this general feeling of, like, Holy shit, they’re letting us do it,” the screenwriter Zak Penn recalled. Feige was a film-school graduate from New Jersey with a storage unit full of movie merch. “Kevin was the kind of guy,” the former executive recalled, “where you would find yourself at a Toys R Us for the release of the ‘Phantom Menace’ toys.” Maisel would debate Feige—whom he described as “Avi’s lackey” at that point—until 3 a.m. over, say, who would win in a fight between the Hulk and Thor. (Maisel leaned Thor: “Strength doesn’t always win.”) On a retreat in Palm Springs, Feige and a small group mapped out “Phase One” of the movies on whiteboards and sticky notes, deciding that it would revolve around the Tesseract, a glowing, all-powerful cube that looks like a design object from the Sharper Image.

Like the Avengers, the group was not immune to squabbling. Avi Arad, several people told me, was excited about the self-producing plan but then turned against it; he worried that they were taking on too much. Perlmutter was also waffling. “Ike wanted to cancel the whole thing. Avi didn’t like it. They realized there was pressure on them to deliver,” the former executive recalled. “It’s like when a kid is trying to date an older girl. All of a sudden, she says yes—well, now what? ‘I don’t know how to take her to prom! I don’t even have a suit!’ ”

A power struggle erupted between Maisel and Arad. “Being in a room with the two of them was like being in a room with a divorcing couple,” Turitzin recalled. In Maisel’s telling, Perlmutter was forced to choose between them, like an Old Testament patriarch. He sided with Maisel. Arad told me that he grew frustrated with how large the company had become and objected to a plan to expand into animated features. “I’m a one-man show. One-man show makes a lot of enemies,” he said. As for Maisel—whom he dismissed as an overambitious numbers guy, while ascribing the studio’s reinvention to his own salesmanship and connections—he said, “He was brilliant, but the way he deals with people turned out to be a problem, specifically for me.” Arad resigned in 2006, and he and his son set up their own production company, which continued to work on Sony’s Spider-Man films. Maisel became the chairman of Marvel Studios. He made Feige head of production.

To direct “Iron Man,” Marvel hired Jon Favreau, who was best known for the single-dude comedy “Swingers” and the Christmas hit “Elf.” The title role came down to Timothy Olyphant and Downey, who was in a career slump after years of drug arrests and rehab. “My board thought I was crazy to put the future of the company in the hands of an addict,” Maisel said. “I helped them understand how great he was for the role. We all had confidence that he was clean and would stay clean.” The movie, with a budget of a mere hundred and forty million dollars, relied less on spectacle than on Downey’s detached playfulness and his screwball-comedy chemistry with Paltrow. When Perlmutter visited the set, the producers had to hide the free snacks and drinks for the crew. Obsessively press-avoidant, he showed up at the première disguised in a hat and a fake mustache."