Je me joins aux éloges faites à cette très sympathiques série, très dynamique, chaleureuse et drôles, aux personnages truculents et aux costumes remarquables et remarqués, chose rare de mon coté.

Je vais en profiter pour faire un petit point sur les mutations de la fiction puisque, hasard de visionnage, j’ai vu cette série à la suite des dernières saisons de true detective et de fargo, soit trois séries dans l’air du temps qui en déploient l’idéologie pour autant que l’idéologie soit bien aussi un certain type de fiction.

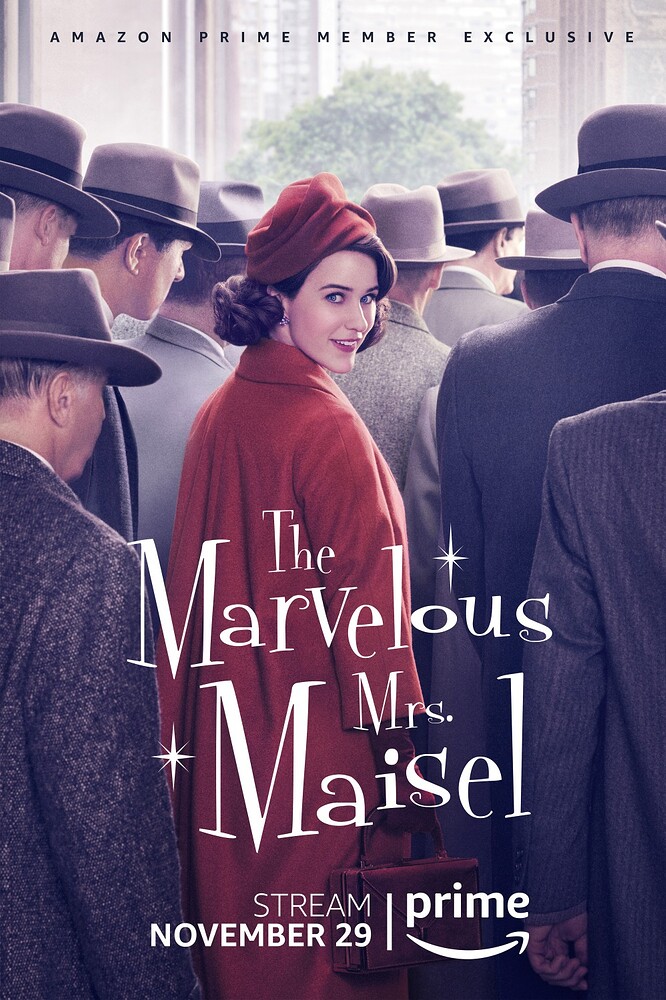

Trois séries dont les persos principaux sont des femmes et lorsque Fargo et true detective confrontent leurs héroines à ce qui s’appelle désormais la masculinité toxique, Mme Maisel ainsi que Fargo ont cette caractéristique de mettre en scène des héros parfaits dès leurs introductions.

J’avais déjà pointé ce type de personnage au sujet d’un épisode what if du MCU mettant en scène une amérindienne en faisant valoir deux éléments :

-

le perso parfait fait tout mieux que tout le monde sans apprentissage aucun ou dés son apprentissage.

-

le perso étant parfait, il ne peut poser aucun acte si on entend par acte, un événement qui change le personnage lui-même ou le monde.

Au titre de l’acte impossible, j’avais d’ailleurs pointer que l’épisode du MCU ne pouvait avoir de sens qu’à la condition que le spectateur sache l’histoire véritable, seul façon pour qu’un acte soit réintégré à la fiction dans sa comparaison avec l’histoire. A ce niveau là, j’incluais l’épisode dans ces fictions qui cherchent n’ont pas à traiter le traumatisme mais à l’effacer ; un type de fictions dans lesquelles j’inclue Avatar et Black Panther, mais aussi un certain type d’esthétique, sans bien arriver à le démontrer encore, des esthétiques à mes yeux ktich, comme celle du MCU en générale, celle de la série Ashoka ou encore celle de the batman, soit des esthétiques creuses, en toc et quelque part parodiques.

Si j’avais pu donc me montrer très critique concernant l’épisode du MCU, Mme Maisel, à l’instar de Fargo et true détective, a ceci de très intéressant qu’elle démontre la possibilité de réaliser de très bonne série dans l’idéologie de l’époque et pour Fargo et Mme Maisel, avec le personnage parfait, ce qui n’est pas une mince affaire puisque c’est donc un personnage qui ne peut connaitre aucune évolution et partant aucune identification. Aucune identification ? A moins que ? C’est ce que nous allons voir.

J’ai déjà exposé ce que j’entends par lecture structurelle d’une histoire, à savoir définir la fiction non par ce qu’elle raconte mais par sa structure et de voir ainsi comment la structure détermine ce qui est raconté.

Le point final d’une histoire fixe rétroactivement le sens définitif de l’acte qui a lieu durant l’histoire. et fait l’identification aux personnages. C’est ce simple fait de structure qui permet de distinguer le à suivre, qui se caractérise de n’avoir pas de point final et donc aucun sens assignables aux actes qui parsèment l’histoire.

Prenons la série Oz par exemple. Dès le premier épisode de cette série sans personnage principal, croit-on, est introduit une personnage qui va se faire violer. Voilà un acte traumatique. Quel sens à cet acte pour le personnage ? Plus tard, le personnage tombera amoureux d’un homme, un autre prisonnier et découvre son homosexualité. Voilà le trauma du viol qui change de sens et ouvre sur une autre histoire, une histoire d’amour ? Plus tard encore, le personnage libéré de prison se fait trahir par son compagnon pour qui souhaite le voir revenir en prison. De nouveau, l’acte initial change de sens, et devient prélude à une tragédie. Plus tard encore, voilà qu’ils se remettent en couple, et le sens bascule à nouveau.

Si la série ne devait jamais finir, le viol comme acte, verrait ainsi son sens constamment remanié, virtuellement à l’infinie. Ce en quoi je dis que le à suivre ouvre sur le hors sens de l’acte et l’impossibilité de lui en fixer un.

Dans une structure finie, c’est le dévoilement du sens de l’acte qui fait la dynamique de l’histoire et qui mobilise les affectes du spectateur, soit son identification. Le dévoilement du sens, c’est par exemple dans la comédie romantique, les amoureux se rendant compte du quiproquo qui les tenait séparés. Le sens de leur rencontre se fixe dans la résolution finale. Le dévoilement du sens, c’est aussi la mort héroïque, dont l’héroïsme dépend du fait que la finalité de la lutte soit acquise, sinon la mort ne serait que vaine et absurde.

Or, revenons à Mme Maisel et aux personnages parfaits, dont on a dit qu’ils ne pouvaient connaitre aucun acte, définition que nous avons donné au terme parfait. Comment fonctionne ici le sens de l’histoire et les émotions qu’il mobilise en l’absence d’acte ?

Premier enseignement de Mme Maisel : ce sont les personnages secondaires qui assurent l’évolution de l’histoire. Fascinant de voir dans la série le travail réalisé sur tous les personnages secondaires, vraiment très réussis, qui tous s’avèrent bien plus riches et complexes que l’héroïne et qui tous vivent bien plus de chose qu’elle, Mme Maisel traversant immaculée sa propre histoire.

Si Mme Maisel n’avait pas été parfaite, aurait pu, par exemple, être questionné son propre rôle dans l’implosion de son mariage. La perfection, après tout, c’est assez chiant. N’y avait il pas là quelques éléments pour rendre intéressant le personnage et le développer ? Le mari voyant éclore sa femme, n’aurait il pas pu lui dire qu’il ne l’aurait jamais quitté si elle avait été comme cela lors de leur mariage, libre et non soumise ? Sauf que non, puisqu’elle était déjà comme ça, faut-il croire, puisqu’elle est parfaite. Il y a d’ailleurs là un petit forçage scénaristique puisque soumise, elle l’était pourtant mais cela ne sera pas adressé.

Est ce à dire donc que le spectateur ne peut s’identifier à Mme Maisel et ne peut vibrer pour elle ?

Pourtant, non.

Et c’est le second enseignement que je tirerais de Mme Maisel : que raconte l’histoire de la série ?, Qu’est ce qui y est mis en scène ? Le perso parfait est un personnage qui n’a aucun défi à relever puisqu’il est parfait et qu’il les a tous déjà relevé dés avant le début de son histoire (pour autant qu’on considère son trauma initial comme une origin story à la manière d’un super héros, c’est à dire comme découpée de l’histoire elle-même) ? Et bien le perso parfait attend d’être reconnu.

Cela fait du personnage parfait un parfait véhicule pour les histoires de femme brillante confrontée à la cécité d’un patriarcat aveugle à sa perfection. C’est donc la faute de l’Autre. De même que les autres, les personnages secondaires, vivaient une histoire avec un sens, de même la faute est renvoyée du coté de l’Autre. Acte et sens sont du coté de l’Autre et pas du sujet. Pas de péché originel avec le personnage parfait, mais un monde gnostique, contrôlé par un démiurge mauvais (ici le patriarcat). Pas d’acte donc pour le perso parfait mais un moment attendu : celui de la reconnaissance. Pure dépendance au regard qui peut reconnaître le sujet.

Une pure reconnaissance sans sens. D’ailleurs, il n’y a aucune histoire à raconter après ce point là.

Idéologie très questionnable. Voilà une morale qui ne sera pas sans effet que celle qui postule la perfection d’un sujet et la faute de l’Autre qui ne le reconnait pas, lui sujet minoritaire et l’Autre atteint de quelques phobies systémiques.

Mais en terme d’identification, c’est un vecteur irrésistible que cette attente du moment scopique de la reconnaissance, qui ne changera ni le sujet, ni le monde mais qui débouche sur la jouissance d’une pure affirmation d’identité via le regard de l’Autre. Le personnage parfait est parfait pour l’age identitaire.

Une dernière chose qui n’est pas sans intérêt pour comprendre l’époque. Dans ce dispositif, ce qui fait couple avrc le sujet est le regard qui aura su voir sa perfection. La reconnaissance initiale de l’Autre dont on attend la répétition pour que se clôt l’histoire, est l amour. Qu’est ce qui est ainsi promu alors comme relation amoureuse la plus sincère si ce n’est celle du pygmalion ?

Émouvant final d’ailleurs, qui voit le matin se transformer en soir pour les rires attendus et qui boucle la boucle.

Mais voyez comment dans la fiction est promue comme amour le plus pur ce qui est par ailleurs décrié hors fiction comme grooming (c’est d’actualité) ou relation de domination (comme celle racontée avec justesse par Judith Godrèche ). Hors fiction vraiment ?

Disons plutôt ceci : c’est la même structure (de fiction) qui dit à la fois l’amour et l’horreur.

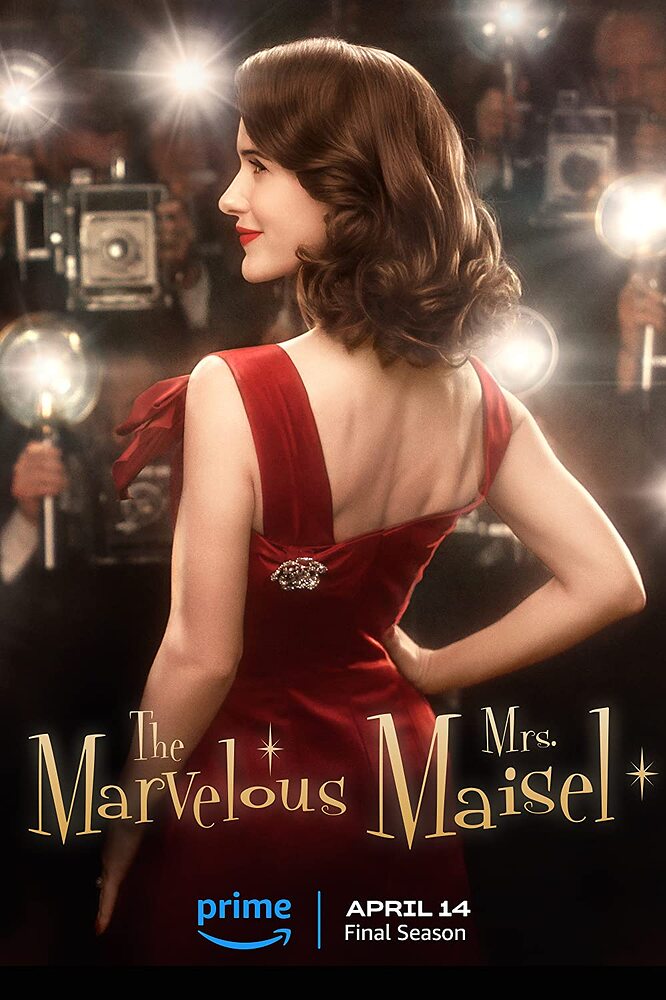

![The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Season 1 - Official Trailer [HD] | Prime Video](https://forum.sanctuary.fr/uploads/default/original/4X/a/d/3/ad33eecb45ca2f065e29be9903634106072218d8.jpeg)